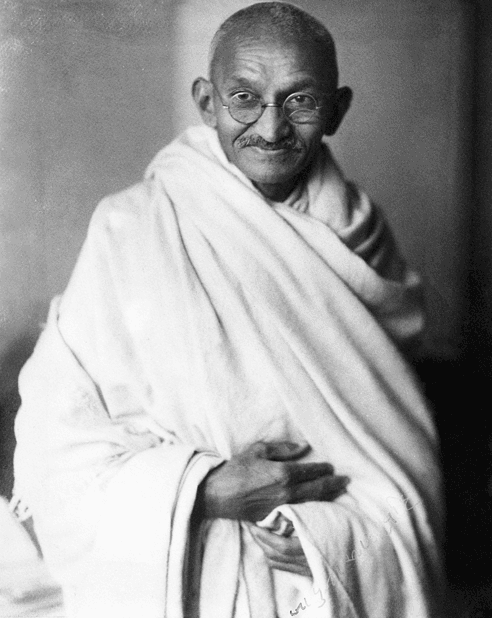

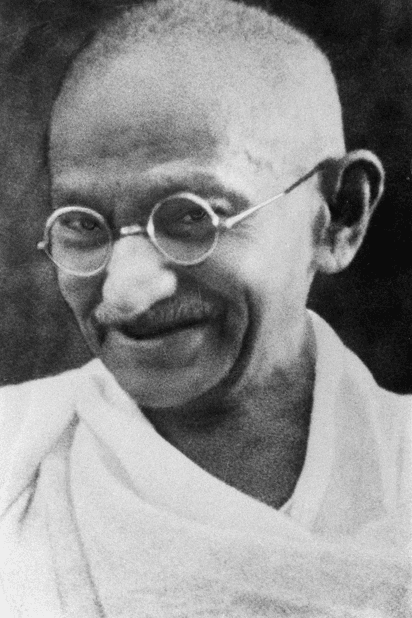

Tomorrow, October 2nd, is the birthday of one of the most prominent Yogis of the past century: Mohandas K. Gandhi, more widely known as Mahatma Gandhi.

While most remember him as the leader of India’s independence movement, Gandhi’s conviction for political freedom was inseparable from his conviction for personal liberation and the dignity of all people everywhere.

His birthday comes just a week after the UN General Assembly. It feels like an important moment to pause and reflect: what does it mean to be a Yogi engaged in the affairs of the world?

For Gandhi, politics was simply the outer expression of his inner practice. He drew his deepest strength from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Bhagavad Gita, as well as from the teachings of Jesus in the Gospels.

For those who have forayed into the Yoga Sutras, you’ll know the Yamas and Niyamas are the ethical foundations of yoga. Gandhi built both his personal discipline and his political movement on the principles of Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truth), Brahmacharya (self-restraint), Aparigraha (simplicity), Sauca (cleanliness), and Tapas (discipline). Two principles stood out for him above all others: Ahimsa and Satya.

Ahimsa – Love at the Core

Ahimsa is usually translated as non-violence, but to me at its core it is Love. In Yoga, the ultimate goal is to realise who we really are. To see who we are when we strip away the labels and roles that cover our essential nature. As our practice deepens, these excess layers begin to dissolve and we begin to touch our love-centered core. We start to feel our oneness with other people, cultures, animals, and the natural world.

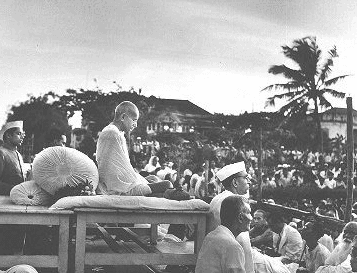

This universal love was at the heart of Gandhi’s political work. He was clear, he and his fellow freedom fighters could not respond to oppression with the same closed-heartedness that drove the British colonisers.

For Gandhi, Ahimsa was not only a refusal to strike back physically, it was about kindness in thought and word to everyone, including his oppressors. His opponents, too, were expressions of the same oneness. He insisted that his followers cultivate goodwill toward their adversaries, believing that only through this deeper discipline of the heart could true change take place within a spiritual aspirant, and for transformational social change.

Gandhi was deeply inspired by the Sermon on the Mount:

“Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you. Bless those who curse you and pray for those who treat you badly. To the one who strikes you on the cheek, turn the other cheek; to the one who takes your coat, give also your shirt.”

Seems like a tall order! But it wasn’t about being weak and capitulating to those who hurt you. It was a response of great strength that was built on deep self love, dignity and compassion for all parties. It came from the understanding that when we hurt others, we do so due to a constriction of love in the heart, and this constriction can ultimately only be released by Love.

Satya – Truth in Action

Equally central was Satya, truth. For Gandhi, truth meant more than personal honesty. It meant naming injustice and refusing to comply with laws that violated human dignity, no matter the cost. His campaigns of civil disobedience were acts of truth. To obey an unjust law, he said, was to participate in untruth.

Satya demanded both transparency and courage, the willingness to speak truth to those with power, and then to stand steady in the consequences.

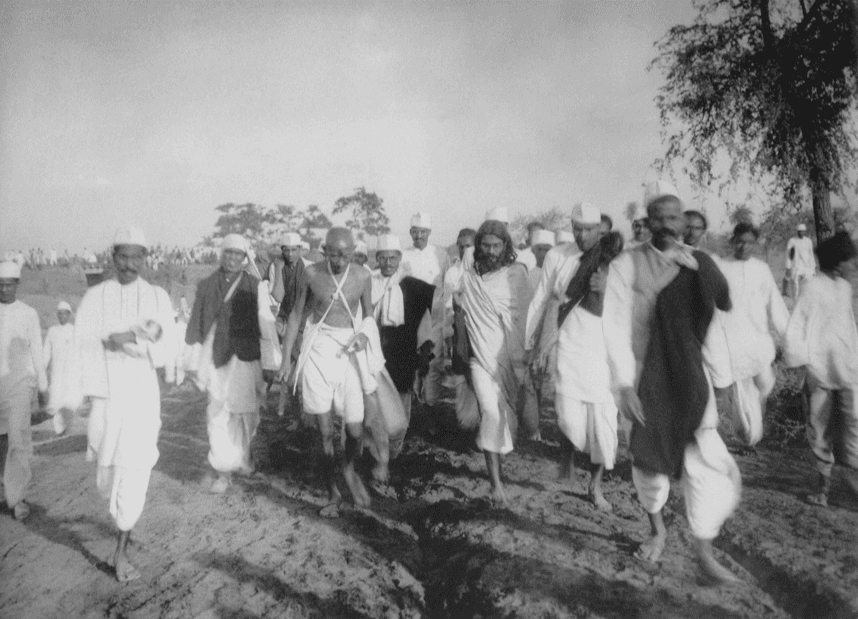

When Ahimsa and Satya were combined, Gandhi called it Satyagraha, “holding fast to truth.”

Satyagraha in Practice

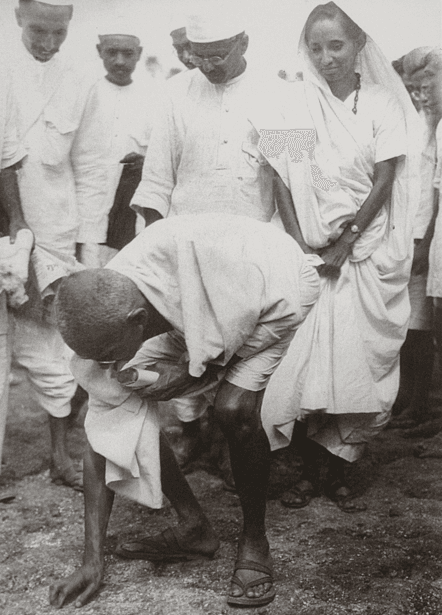

One of the most powerful examples was the Salt March of 1930. At the time, the British forbade Indians from collecting or selling salt, forcing them to buy heavily taxed imports. Gandhi led tens of thousands of people to the sea to make their own salt, defying the law. Protestors of all backgrounds joined in, and thousands were beaten mercilessly by police. The protesters however were trained to endure violence without retaliation or hatred. Around 60,000 people were jailed during that campaign.

Why endure such suffering without striking back? Gandhi’s answer was simple: “An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.” He trained his followers in love and non-violence as soldiers are trained for the military. But instead of training them in violent combat and to maintain loyalty to a tribal identity, he taught his fellow freedom fighters to endure suffering and respond with dignity and compassion.

Reflections for Us

I find this history remarkable. Having worked in social justice, I’ve felt anger and despair toward those who drive war, environmental destruction, and human rights abuses. Gandhi challenges me to ask: what does it mean to confront violence and injustice with courage, while holding no animosity toward those inflicting harm? How do we stay empowered and hopeful in the face of Goliath-sized national and world issues? It’s easy to talk about big ideals, but quite demanding in practice.

What I love about Yoga is that it asks us to practice these same questions in our personal lives. We start where we are at. As we learn to practice these principles in our own relationships, we naturally extend them outward. The path of Yoga ultimately leads us beyond the narrowness of personal identity into service, into Karma Yoga, where our practice is offered to the wider world.

We don’t have to live in a country at war or under oppression to understand this. Each of us has been hurt through betrayal, discrimination, and unfair treatment. And our habitual responses are familiar: anger, shame, fear, denial, or bypassing our pain.

But when we can remain steady and clearly speak the truth about the hurt that has been inflicted upon us, and simultaneously face our pain with compassion for ourselves and the person who hurt us, a new freedom opens up.

Those who hurt us may still cause real material consequences, but they no longer hold the same power in our minds. By giving ourselves the dignity, compassion and affection we seek, we are no longer psychologically hooked. We can now respond to the harm inflicted by others, not from a place of us feeling inadequate, but from a place of equanimity where we can see the other person’s limitations.

This doesn’t mean we don’t hold boundaries, respond with fierceness or demand accountability, because sometimes that is what is necessary. It simply means our response is no longer driven by bitterness, which weakens the heart, but by love grounded in truth.

Extending Our Practice

It is heartbreaking to see the major human rights violations today in Gaza, Sudan, Venezuela, Ukraine, and many other parts of the world. But instead of sinking into despair, Yoga calls us to clear up our mind, ground ourselves in positive intention and take action without attachment. To me this means to be informed, to dig deep to see what we can do within our capacity (which often is more than we realise!). And to keep our hearts open with compassion for all our fellow beings – because we are all connected at the level of the soul.